How research helps guide and evaluate ecological restoration

Restoration and research have much to gain from one another. Restoration interventions are experiments at an uncommonly large scale that offer researchers unique opportunities to better understand the inner workings of ecosystems. Research, in turn, can facilitate better planning, implementation, and evaluation of restoration projects. Our research relating to restoration aligns with three broad themes – understanding where and what to restore (see Whittled-down woods), tracking revival in restored ecosystems, and testing and refining restoration methods.

Tracking ecosystem revival

Forests with slow-growing and long-lived trees can take decades to centuries to recover from disturbance, whether through natural processes alone or with a helping hand from restoration. Studies conducted 10-20 years after restoration can shed light on whether restored forests have begun the journey towards comprehensive recovery. To evaluate this in context, one needs to compare restored forests to areas that were similarly degraded to begin with but were not restored, and mature, minimally-disturbed, benchmark ecosystems. The former comparison reveals how far restoration has pushed the ecosystem along the path of revival, and the latter, how far is left to go. Since 2016, we have conducted and published a number of studies assessing the recovery of ecosystem structure, trees, birds, and ecological processes such as seed dispersal and regeneration across 25 restoration sites in the Anamalai Hills. We see differences in how well each indicator is recovering, but a common message does emerge: restoration can have a positive impact, especially in more isolated and degraded fragments, but standing intact forests harbor irrecoverable biodiversity and ecological values, and their protection should be the first priority.

Testing restoration methods

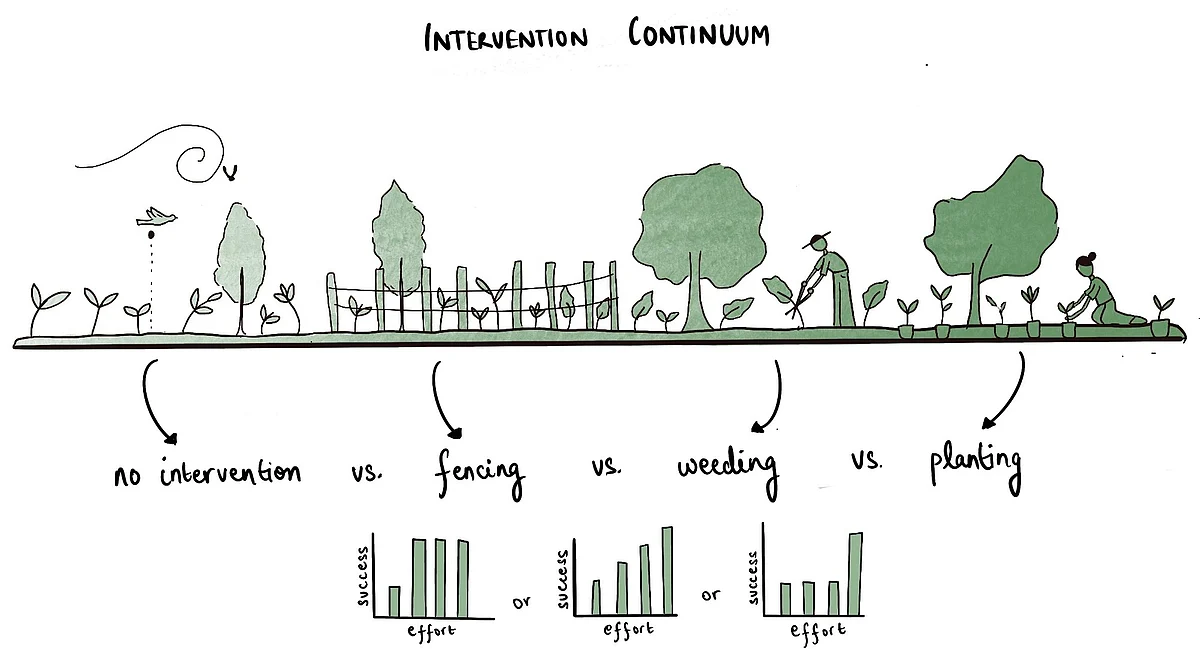

A challenge for restoration practitioners is to design interventions that are appropriate and likely to succeed, while controlling costs. This requires information on how outcomes change as costs increase along an intervention continuum, which can range from low-cost steps to protect sites and let nature take its course, to intensive and costly interventions such as invasive species control, soil engineering, and tree planting. In the Anamalais, initial experiments with invasive species removal helped shape our restoration strategy. We found that completely removing alien invasive species is best for stimulating survival and growth of the planted trees and avoiding re-invasion; by contrast, less intensive approaches such as clearing invasives only around planted trees proved quite ineffective.

In other ongoing studies in the Anamalais and central Western Ghats, we are experimenting with direct seeding – a method of introducing target species by sowing their seeds in restoration sites. Our goal is to identify native tree species for which direct seeding works well, and compare this method to other restoration methods under different site conditions. Learnings from such experiments help us review and refine our restoration approach, and contribute to the quest for cost-effective and scalable restoration solutions.

Collaborators

Alumni: Akhil Murali, Jyotsna Nag, Mrinalini Siddhartha, Vena Kapoor